By: Nicole Silberstein

Despite some recent high-profile failures, food retailers still clearly believe that successfully reducing food waste has financial and competitive upsides that make it worth the fight.

In this ongoing series, Schieber Research is focusing in on companies and organizations that are creating impactful change on the issue of food waste and looking at industry innovations that are aiding them in their efforts. Here we dive into the retail side of the equation. Take me to “Part 1: The Food Waste Problem” first.

Grocers around the world are leading the charge in the fight against food waste – unfortunately, recent headlines would appear to indicate that they’re not having much success.

In May, British supermarket chain Sainsbury’s announced that it was axing its £1 million Waste Less, Save More trial initiative in the English town of Swadlincote, which tested a host of different ways to cut food waste and save consumers money, from handing out free smart refrigerators to opening community pantries for unsold food. After three years, only a 9 percent reduction in food waste was recorded, well short of the 50 percent target.

Just a month before that, the U.S. non-profit Center for Biological Diversity, graded America’s top retailers on their food reduction efforts, and only Walmart scored a B. Six of the 10 got a D or F including Target, Costco and Whole Foods.

Meanwhile, the U.K.’s largest retailer, Tesco, which has been a pioneer in food waste reduction efforts, just announced that it fell short, very short, of its goal to completely eliminate edible food waste in its operations by February of this year. Instead, the company’s food waste footprint actually increased by more than 6,000 metric tons.

Are Grocers ‘Inherently Wasteful’?

“Tesco’s failure to eliminate food waste completely in its own operations – let alone in its supply chain or in its customers’ homes – despite its undisputed leadership and its commitment to doing do, suggests to us that supermarkets’ business models and ownership structure make them inherently wasteful,” said Carina Millstone, executive director of the UK charity Feedback Global. “We look forward to Tesco proving us wrong.”

And they intend to. In fact, despite missed milestones and lackluster results, not one of these retailers is dropping their food waste reduction efforts. But why, given the apparently Sisyphean nature of the task?

The answer is simple – because the rewards for success are simply too big to ignore.

The Profit and PR Potential

As we mentioned in the first article in this series, food waste costs the world $990 billion every year. Adding even a fraction of that back to the bottom line would be a huge win, particularly for companies operating in competitive sectors with tight margins (like grocery).

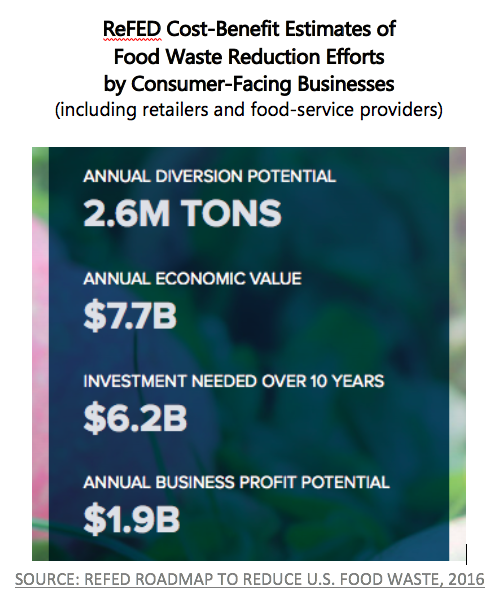

The food waste-focused non-profit Rethink Food Waste through Economics and Data (ReFED) estimates in its Roadmap to Reduce Food Waste that implementation of food waste prevention and recycling solutions has the potential to result in $1.9 billion of profit from revenue and cost savings. These solutions include consumer education campaigns, standardized date labeling and waste tracking.

The food waste-focused non-profit Rethink Food Waste through Economics and Data (ReFED) estimates in its Roadmap to Reduce Food Waste that implementation of food waste prevention and recycling solutions has the potential to result in $1.9 billion of profit from revenue and cost savings. These solutions include consumer education campaigns, standardized date labeling and waste tracking.

And there’s another, less measurable advantage to taking on the challenge of food waste – in crowded markets like retail, social responsibility initiatives can give companies a competitive edge.

A 2017 study by Cone Communications, showed that 78% of Americans want companies to address important social issues. In fact, awareness of the food waste issue is increasing at such a rate that not making some effort at reduction might very soon become detrimental to companies operating in the food sector.

Earlier this year several of Amazon’s largest investors asked the Securities and Exchange Commission to force the company to release information about the amount of food waste in its operations. Amazon had brushed off previous direct requests from shareholders, saying that food waste “wasn’t material.” The shareholder request was eventually blocked by the SEC because food represented less than 1% of Amazon’s budget in 2017 (although that may not remain true for long as the company continues to expand its Whole Foods business). Now, an operation of Amazon’s size and scope might be able to get away with such nonchalance, but not many other companies can afford to show such blatant disregard for the concerns of their stakeholders.

Grocers’ Power Position

And the fact is that grocers are in a particularly powerful position to reduce food waste, not just in their own operations but across the food chain, although it might seem that way at first glance.

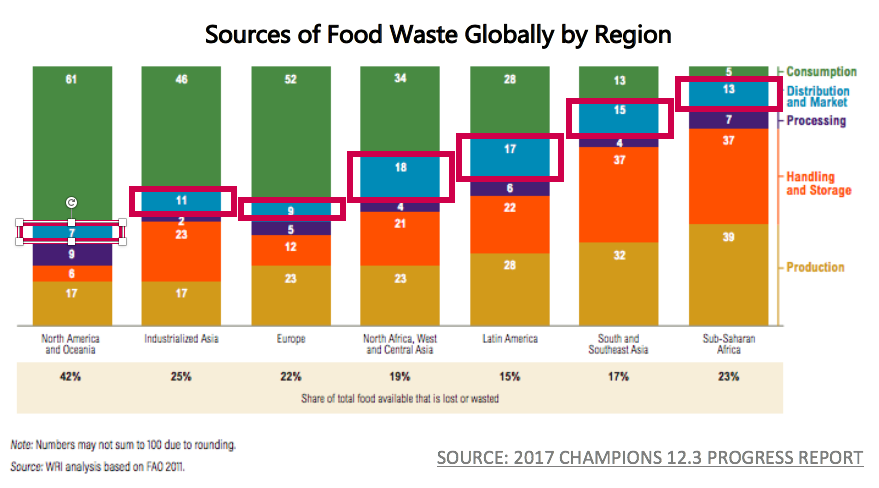

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that in North America and Oceania, the Distribution & Market segment of the food chain accounts for the second smallest portion of Food Loss and Waste (or FLW), just 7 percent of the total in that region. In fact, around the globe, regardless of whether you’re looking at industrialized or less-developed regions, one thing is clear – retailers are not the biggest part of the problem.

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that in North America and Oceania, the Distribution & Market segment of the food chain accounts for the second smallest portion of Food Loss and Waste (or FLW), just 7 percent of the total in that region. In fact, around the globe, regardless of whether you’re looking at industrialized or less-developed regions, one thing is clear – retailers are not the biggest part of the problem.

But here’s why food retailers matter, perhaps more than anyone else in this equation – grocers, especially large national and multi-national chains, have influence that stretches well beyond their own segment of the food chain. They can impact FLW not only in their own operations, but also among their suppliers on the production side and their consumers at the other end.

Tesco has been working both sides of the equation for several years, with mixed results. For example, the company employs enhanced forecasting and ordering systems to manage bumper crops (crops that produce more than expected quantities) and offer multi-buy promotions on produce from those crops. Sometimes this works out great, like with this August’s Bank Holiday Bumper Berry Bonus, but sometimes the customer doesn’t hold up their (albeit unwitting) end of the bargain by buying all that excess, and the problem just gets pushed down the supply chain. In fact, Tesco pointed to these attempts to help farmers reduce their food waste as one of the reasons its own food waste increased.

Which begs the question, was Millstone right? Is there something inherently wasteful about the grocery business that can’t be changed? The truth is we don’t know for sure yet. What we do know is that the task is incredibly challenging, but there have been successes.

The Success Stories

There are a lot of caveats to the dire headlines we summarized at the start of this article – Tesco actually had a not unimpressive 64% reduction in edible food waste, but because food sales were up at the same time, that reduction didn’t translate into the overall tonnage of food wasted (none of which, by the way, ended up in a landfill, but instead was converted into energy sources).

which, by the way, ended up in a landfill, but instead was converted into energy sources).

And while Sainsburys did scrap the larger Waste Less, Save More initiative, several of the more successful elements, such as the Community Fridge Network, will live on and actually be expanded. The campaign was also very successful in raising consumer awareness with 64 percent of Sainsbury’s customers in Swadlincote saying they had already or were planning to change their behavior to cut food waste. An impressive number, given that ReFED estimates consumer education to be the single most cost-effective tactic in the fight against food waste.

Let’s take a look now at some of the other success stories in this battle, because there are many:

Turning surplus groceries into meals. Tesco has diverted the equivalent of 16 million meals of surplus food to 6,000 charities across the UK since 2012 through its work with the charity FareShare. And they’re not alone – Aldi, Amazon, Kroger and many others also have programs in place to donate surplus edible food. Walmart donates some of its food waste to Ecoscraps, which turns it into plant food (compost, potting mixes and plant foods) that is then sold at Walmart and other retailers.

Turning surplus groceries into meals. Tesco has diverted the equivalent of 16 million meals of surplus food to 6,000 charities across the UK since 2012 through its work with the charity FareShare. And they’re not alone – Aldi, Amazon, Kroger and many others also have programs in place to donate surplus edible food. Walmart donates some of its food waste to Ecoscraps, which turns it into plant food (compost, potting mixes and plant foods) that is then sold at Walmart and other retailers.- Reacting faster with AI. Walmart’s new AI tool Eden (developed in-house) will inspect produce to monitor shelf life and predict spoilage with the resulting cost savings estimated at $2 billion in food waste over the next five years. Eden has already prevented $86 million in waste since it was deployed at 43 food distribution centers in January 2017. The system also incorporates tracking devices on produce to monitor temperature during travel and will be able to react to anomalies to avoid wastage like rerouting to a closer location if temperatures spike. Walmart also plans to expand the system to its farmers in the near future.

- New ways to extend shelf life. U.S. grocer Stop & Shop realized that large piles of produce, while believed to be more attractive to consumers, were actually increasing spoilage rates. By decreasing the size and style of their displays, the retailer reported savings of $100 million annually with minimal impact on consumer experience. A number of retailers are also working with suppliers to develop innovative new packing solutions that extend produce shelf life.

- Getting over the idea that produce has to be pretty. Walmart, Tesco, Asda and Intermarché

are only some of the major grocers offering “ugly” produce – that is, food that is edible but has cosmetic flaws – at reduced prices. When French supermarket Intermarché debuted its Inglorious Fruits & Vegetables line in March 2014, the retailer saw a 24 percent increase in store traffic, which it attributed to the campaign. Tesco estimates that its Perfectly Imperfect line has saved more than 6,000 metric tons of produce from going to waste.

are only some of the major grocers offering “ugly” produce – that is, food that is edible but has cosmetic flaws – at reduced prices. When French supermarket Intermarché debuted its Inglorious Fruits & Vegetables line in March 2014, the retailer saw a 24 percent increase in store traffic, which it attributed to the campaign. Tesco estimates that its Perfectly Imperfect line has saved more than 6,000 metric tons of produce from going to waste. - Standardizing date labels. In a recent survey from the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic, almost 85 percent of consumers said that they’d thrown out food based on the date on the package. However, in many cases, the dates on packaged food have nothing to do with how safe the food is, but rather a best guess as to how long the food will taste its freshest. Not to mention that many consumers are understandably confused by the distinctions between “Best

if used by” and “Sell by” dates, and how they should respond once food passes these timeframes. To combat this, many retailers are working to standardize and simplify their date labeling practices, and Tesco is eliminating date labels completely from many of their products. Sainsbury’s has been testing out a new kind of smart label on its house brand ham that changes color depending on how long the pack has been open and the temperature at which it’s been kept, rather than featuring a hard date.

if used by” and “Sell by” dates, and how they should respond once food passes these timeframes. To combat this, many retailers are working to standardize and simplify their date labeling practices, and Tesco is eliminating date labels completely from many of their products. Sainsbury’s has been testing out a new kind of smart label on its house brand ham that changes color depending on how long the pack has been open and the temperature at which it’s been kept, rather than featuring a hard date. - Helping consumers moderate portions. Another holdover from Sainsbury’s defunct Waste Less, Save More campaign is snapback packaging that allows consumers to reseal products, keeping them fresh longer and resulting in a 75 percent reduction in food waste.

In this ongoing series, Schieber Research will focus in on companies and organizations that are creating impactful change on the issue of food waste – including food manufacturers, restaurants and consumers – and look at industry innovations that are aiding them in their efforts. Stay tuned soon for the next installment.